In remembrance of all our brave sisters who left Brabant in the “Great Mission Hour”, we tell the tale of Sister Trinitas

The spread of God’s word

This is a tale as old as Christianity itself.

Jesus told his disciples: “As the Father has sent Me, so I also send you”. This rallying cry fell in fertile soil in the Catholic South of the Netherlands. From 1895 hundreds of women left from Sancta Monica Monastery in Esch in Brabant, the Motherhouse of the congregation in the Netherlands. Between 1900-1960, North Brabant had the most Dutch congregations and was a “top supplier” of missionaries. It is not without reason that this period is called the Great Mission Hour. One of those missionaries was Sister Trinitas.

Jesus told his disciples: “As the Father has sent Me, so I also send you”. This rallying cry fell in fertile soil in the Catholic South of the Netherlands. From 1895 hundreds of women left from Sancta Monica Monastery in Esch in Brabant, the Motherhouse of the congregation in the Netherlands. Between 1900-1960, North Brabant had the most Dutch congregations and was a “top supplier” of missionaries. It is not without reason that this period is called the Great Mission Hour. One of those missionaries was Sister Trinitas.

Gertrudis Koop (Sister Trinitas, 1912-1999) came from a religious and socially motivated family. She was seven years old when she read missionary diaries about African children and decided that she wanted to do something about that when she grew up. At the age of 19 she felt called to become a Religious Missionary, entered the postulate and started her formation with the White Sisters, in the Motherhouse in “Sancta Monica” in Esch. At her First Vows in 1933, Gertrud received the name of Sister Trinitas.

Missionary Sisters of Our lady of Africa

Charles M. Lavigerie (1825-1892), Archbishop of the North African city of Algiers (Algeria), founded the congregation of the Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Africa in 1869. Africa was the cradle of the old Christianity at the time of Saint Augustine (354-430), when the North African coastal strip was still a province of the Christian Western Roman Empire. The dream of Lavigerie was to spread the gospel all over Africa. He saw churches not only on the north coast, but all over the continent. In 1868 he founded the Society of the Missionaries of Africa in Algiers and a year later in 1869, he founded a female branch to reach the Muslim women and their children – the Fathers with a long beard, red fez and a burnous, the sisters with a long white veil. For this reason, they got the nickname White Fathers and White Sisters. Following the spirituality of the founder, they had to be willing to “become all to all” and “not recoil in the face of hardship, not even death itself, to help bring about the Kingdom of God.”

His main instruction to successfully address the proclamation of faith among the African people was: “You must speak their language – eat like them – dress like them”.

Although the congregation was very French in the early years, sisters of other nationalities soon followed. In 1940, two hundred and thirty Dutch White Sisters worked in Africa.

The White Sisters were assigned to various mission stations in North Africa but also in Tanzania, Kenya, DR Congo, Zambia, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda. Here they mainly focused on primary education, household education, religious lessons, health care, care for youth, and particularly care for women and home visits.

The White Sisters were assigned to various mission stations in North Africa but also in Tanzania, Kenya, DR Congo, Zambia, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda. Here they mainly focused on primary education, household education, religious lessons, health care, care for youth, and particularly care for women and home visits.

Sister Trinitas in Malawi

Sister Trinitas received her religious and medical training in the Motherhouse in Esch and in Algiers. In 1940 she was ready to leave for Central Africa. She was advised by her superior: “Be sure there is water, fertile land and start growing so that you can at least eat yourself.” It was a six-week boat trip and World War II had just begun. The boat had to sail in the dark with all windows and curtains tightly closed. It was a dangerous journey; the Mediterranean Sea, the Suez Canal, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean were dotted with mines. Once she arrived safely in Malawi, she learned the local language, Chichewa, and the native customs and culture for the first six months. Then she left for her mission post in the town of Likuni. On arrival, she and several other sisters immediately started providing medical care for local residents and training Malawian midwives.

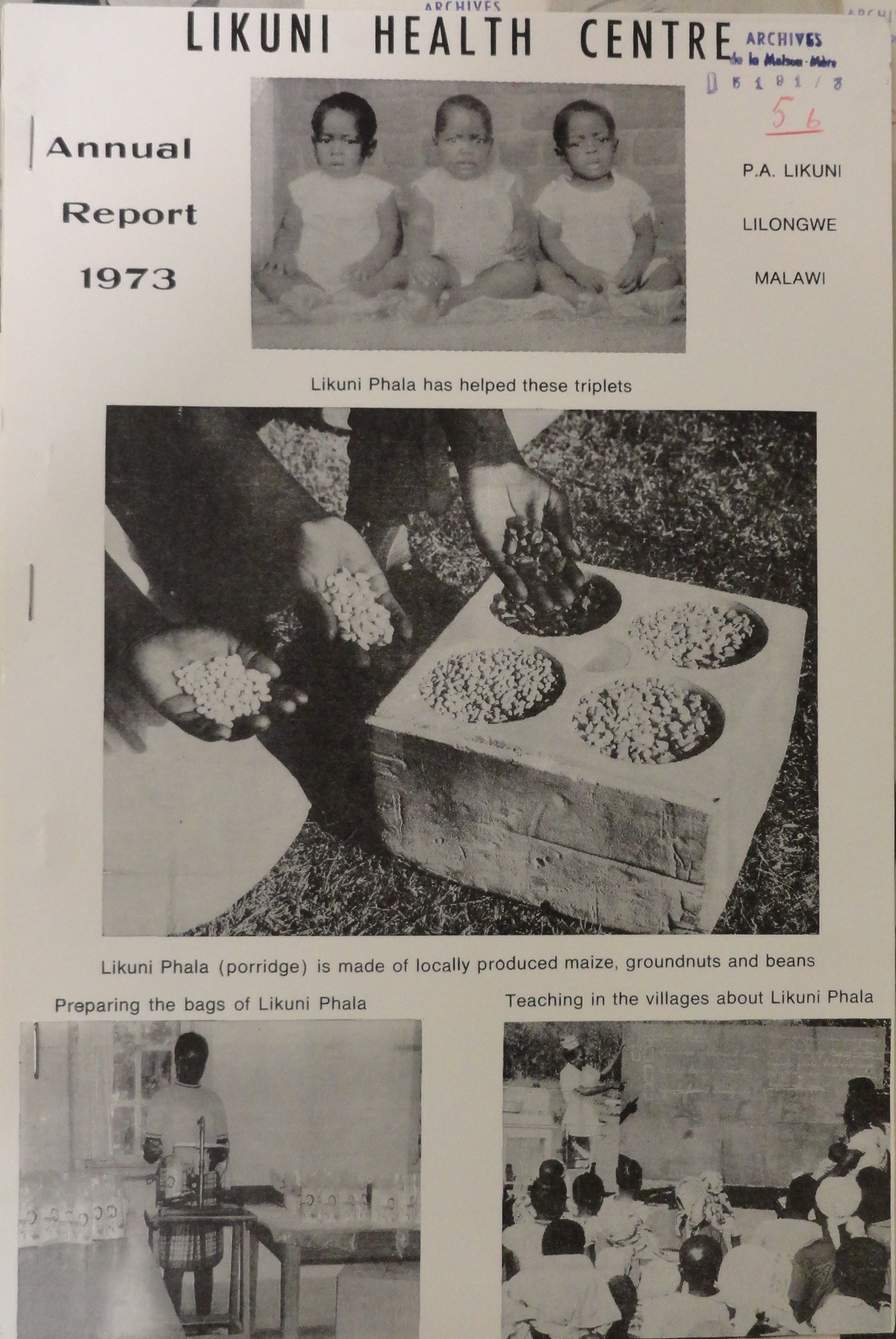

Confronted with the high mortality rate of children in their first year, despite all the efforts in the field of hygiene and pre- and postnatal care, Sister Trinitas started researching and discovered that the children did not die of hunger, because there was enough food. The culprit was in fact protein deficiency. She went on to develop a protein-rich porridge, easy to prepare with local products: two units of corn, one unit of ground-beans and one unit of ground-peanuts mixed with milk or water and some sugar. Likuni Phala (Likuni Porridge) was created in 1968 and after more research, it received the approval in 1978 from the Food & Agricultural Organization (current World Food Program) of the United Nations, as a high quality food product. A factory was built in Malawi and Likuni Phala was produced on a large scale, with the World Food Program being the most important client. The porridge could be made with local products, hence making it affordable for the poorest of the poor.

Confronted with the high mortality rate of children in their first year, despite all the efforts in the field of hygiene and pre- and postnatal care, Sister Trinitas started researching and discovered that the children did not die of hunger, because there was enough food. The culprit was in fact protein deficiency. She went on to develop a protein-rich porridge, easy to prepare with local products: two units of corn, one unit of ground-beans and one unit of ground-peanuts mixed with milk or water and some sugar. Likuni Phala (Likuni Porridge) was created in 1968 and after more research, it received the approval in 1978 from the Food & Agricultural Organization (current World Food Program) of the United Nations, as a high quality food product. A factory was built in Malawi and Likuni Phala was produced on a large scale, with the World Food Program being the most important client. The porridge could be made with local products, hence making it affordable for the poorest of the poor.

After years of dedicated work, she became Principal Nurse and head of the nurses’ and midwives’ course. By then the hospital had 160 beds, but there were often many more patients. Sister Trinitas was very practical; problems were there for her to solve.

Mother for all people

Meanwhile, Malawi had become an independent nation in 1964. Anyone who did not have a Malawian nursing diploma was to leave the country. An exception was made for Sister Trinitas because of her now national fame. Under the dictatorial regime of President Hastings Banda, Sister Trinitas was not afraid to speak up openly. Several times she risked going to prison but she was helped by the wives of men in government circles, whom she had assisted in giving birth. In 1974, the hospital in Likuni was transferred to Malawian staff. Over the years, Sr Trinitas had trained a total of 300 nurses and midwives, and now, at the age of 62 she was transferred to another mission post. This time with a mobile clinic, Sister Trinitas visited remote villages to introduce Likuni Phala and raise awareness about proper nutrition and hygiene to prevent disease. Trinitas was in Malawi as a mother to all people, young, old, rich and poor. “Our work was not hunting for souls. I never got around to that” she said in a newspaper interview.

Times were changing

Around that time, there was an increasing call for ecclesiastical independence. After the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) – on the modernization of the church – the Pope called on African Christians to continue on their own the missionary work and development of the church.

As a result, many Western Sisters return to their homeland in the late 20th century and early 21st century. Those were years of profound cultural changes and the White Sisters could not escape this social criticism despite the fact that they worked with a profound respect for the local culture and managed their activities so as to make themselves superfluous.

Once a missionary, always a missionary!

Just like Sister Trinitas, more than 3.000 women have made their vows as White Sisters, of which approximately 500 from the Netherlands. Today there are still 40 Dutch sisters, all living in the Netherlands. The Dutch Motherhouse “Sancta Monica” in Esch, was sold and most of the sisters moved to a house in Boxtel which has since been turned into a contemporary intercultural and multi-religious center called “Wereldhuis” (World House), in which our Sisters live together with residents of Islamic, Indonesian and Dutch descent. A number of White Sisters also live in Eindhoven, Nuland and Etten-Leur, together with other religious Congregations. Despite their age, they are still committed to their fellow humans and to peace and justice in the world.

Just like Sister Trinitas, more than 3.000 women have made their vows as White Sisters, of which approximately 500 from the Netherlands. Today there are still 40 Dutch sisters, all living in the Netherlands. The Dutch Motherhouse “Sancta Monica” in Esch, was sold and most of the sisters moved to a house in Boxtel which has since been turned into a contemporary intercultural and multi-religious center called “Wereldhuis” (World House), in which our Sisters live together with residents of Islamic, Indonesian and Dutch descent. A number of White Sisters also live in Eindhoven, Nuland and Etten-Leur, together with other religious Congregations. Despite their age, they are still committed to their fellow humans and to peace and justice in the world.

Once a missionary, always a missionary!

This article is based on a longer article written by historian Sabine Ticheloven with the cooperation of Marina van Dalen, coordinator/countrymanager MSOLA-NL. Pictures from the picture book of Sr Trinitas Koop, which is kept in the archives of MSOLA in the Religious Heritage Center in St. Agatha in NL. The original article was published in the provincial heritage magazine InBrabant, 11th year, N° 1 march 2020.